MedCenter Air – Hurricane Season 2017

By @BeachAV8R - October 23, 2017

Originally published at: Articles - Mudspike Forums

This hurricane season has not been kind to Central America, the Gulf of Mexico region, or the Caribbean. MedCenter Air crews, along with hundreds of other flight and medical crews from across the United States and the Caribbean, have been pitching in to help aid with the recovery of those areas touched by the hurricanes. This is only a small part of the story.

Please note - these are only the author’s thoughts and recollections, and do not represent other individuals or entities. Any errors of omission or recollection are mine and mine alone.

Harvey

Our first deployment of the 2017 hurricane season occurred in late August 2017 in the days after Hurricane Harvey roared ashore as a Category 4 storm near Rockport, Texas. After crossing the coast, a stubbornly persistent Harvey stalled, then backtracked toward the Gulf, dumping prodigious amounts of rain across Southeastern Texas and Louisiana.

Once the call from FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) came in, the full resources of Carolinas Healthcare System and MedCenter Air started to gear up in response. MedCenter Air was just one of dozens of air ambulance services (both fixed wing and rotor) called up as teams from across the country started moving equipment, supplies, and staffing toward Southeast Texas. Our base of operations in Texas, along with many other flight teams, would be the airfield in Temple, Texas - far enough from the disaster zone to allow our presence to not be a burden on the immediate disaster area, but within striking distance of the people and facilities we were sent to support.

FEMA requested two aircraft, each with an isolette capability for neonatal patients. Two aircraft were sent: one of our Citation Ultras and a King Air B200. Each plane would be staffed by a pair of pilots and medical crew in day and night shifts, thus requiring a total staffing of sixteen people. Due to the heavy loadout of equipment and personnel, limiting the amount of fuel that could be carried for the trip to Texas, the aircraft had to make a fuel stop at a mid-point. We also enlisted the help of our corporate/organ procurement King Air with additional seats to move additional equipment and crews to Texas.

[caption id=“attachment_8993” align=“aligncenter” width=“476”] Medical crew and equipment loaded into the Citation for the flight to Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_8994” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Medical crew and equipment loaded into the Citation for the flight to Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_8994” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Three aircraft, representing 75% of our fixed wing fleet, ready for the flight to Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_8999” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Three aircraft, representing 75% of our fixed wing fleet, ready for the flight to Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_8999” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] N207CM prepares to depart Charlotte for Temple, Texas by way of Columbus, Mississippi.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_8998” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

N207CM prepares to depart Charlotte for Temple, Texas by way of Columbus, Mississippi.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_8998” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Enroute to our fuel stop in Columbus, Mississippi with the remnants of Harvey still impacting coastal Louisiana, Alabama, and Florida…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9000” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Enroute to our fuel stop in Columbus, Mississippi with the remnants of Harvey still impacting coastal Louisiana, Alabama, and Florida…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9000” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A fast quick turn for fuel in Columbus, Mississippi and we were on our way to Temple, Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9004” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

A fast quick turn for fuel in Columbus, Mississippi and we were on our way to Temple, Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9004” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A portion of the crew that deployed to Temple, Texas (author - tall, goofy guy in center with wrinkled uniform).[/caption]

A portion of the crew that deployed to Temple, Texas (author - tall, goofy guy in center with wrinkled uniform).[/caption]

The three aircraft from MedCenter Air trickled in to Temple, Texas over the next couple of hours as their varying groundspeeds allowed for a bit of gap between their arrivals. Flying the first and fastest aircraft, me and my crew were the first to arrive, pulling on to the FEMA managed fleet ramp at Temple, TX just as the sun was setting. The enormous hangar facility was abuzz with other arriving aircraft, medical crews, pilots, and supplies pouring in to support the fixed wing operations that would kick off the next day. The penalty for arriving first was that we got to dive into the government paperwork required to get our aircraft and crews registered with FEMA.

[caption id=“attachment_9001” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A beautiful sunset just after our arrival at Temple, Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9002” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

A beautiful sunset just after our arrival at Temple, Texas.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9002” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] FEMA paperwork for everyone…![/caption]

FEMA paperwork for everyone…![/caption]

After the other aircraft landed, N207CM disgorged its supplies and headed back to Charlotte while N265CM and N209CM were put to bed to await flights. Crews were divided into Citation day/night and King Air day/night shifts for the duration of the deployment. In a scene that would replicate itself many, many times over the next six weeks as we went from the hurricane Harvey deployment to the hurricane Maria deployment, we would do our version of the clown car, packing as many people and bags into crew vans for trips back and forth to the hotel.

[caption id=“attachment_9003” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A variant of Twister as we pile into the clown car/van.[/caption]

A variant of Twister as we pile into the clown car/van.[/caption]

After getting a night of crew rest, we were held in position at our hotel for one additional day while FEMA worked on the logistics of where and when all of their assembled assets should go. I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t a bit frustrating sitting around while we watched other teams swing into action a bit sooner than us, but we remained available and ready and eventually the trips started funneling our way. Over the course of the week we would fly medical evacuation missions and personnel transports, all combined with some light cargo carrying in conjunction with other movements. As the week wore on, the water crisis in Beaumont, Texas took front and center on the national stage as the inundated city faced the trite adage of “water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink”, necessitating the mass evacuation of patients from hospitals in that area.

[caption id=“attachment_9005” align=“aligncenter” width=“425”] Captains Blanton and Biggers on their first day of school in Temple, Texas.[/caption]

Captains Blanton and Biggers on their first day of school in Temple, Texas.[/caption]

Operations from Temple were impressive as dozens of aircraft from around the country were assembled and dispatched from the airfield. Typically aircraft would be pushed in waves from Temple to Beaumont, where they would sit for a few minutes or hours awaiting a patient to show up. The situation at Beaumont was definitely organized chaos with fixed wing aircraft, dozens of helicopters, and military aircraft and helos of all types running around the airspace on a multitude of missions. It was a unique situation for us MedCenter Air crews, requiring a lot of flexibility and adaptability to changing plans. As well, the medical crews would have little to no idea what type of patient was showing up at the plane, so their assessments were very much on the fly and they handled the unknown with their typical professional calm. Unlike what we would later face in Puerto Rico, ATC and communications were generally very good throughout Texas, allowing for a good bit of normalcy to the to the actual flight conditions.

[caption id=“attachment_9006” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] N209CM prepares to launch from Temple for a transport out of Beaumont, Texas[/caption]

N209CM prepares to launch from Temple for a transport out of Beaumont, Texas[/caption]

One of the unique challenges for MedCenter Air crews during the Harvey deployment was an extremely odd schedule that was tough to adapt to. Day pilots were assigned a shift from 2PM to 2AM, while night pilots (including me) were on duty from 2AM to 2PM. As a result, there really was no true “day” or “night” shift since you spent a good bit of time on both. Finding rest during the rest periods was a bit of a challenge on such an odd schedule, but we all adapted and did our best.

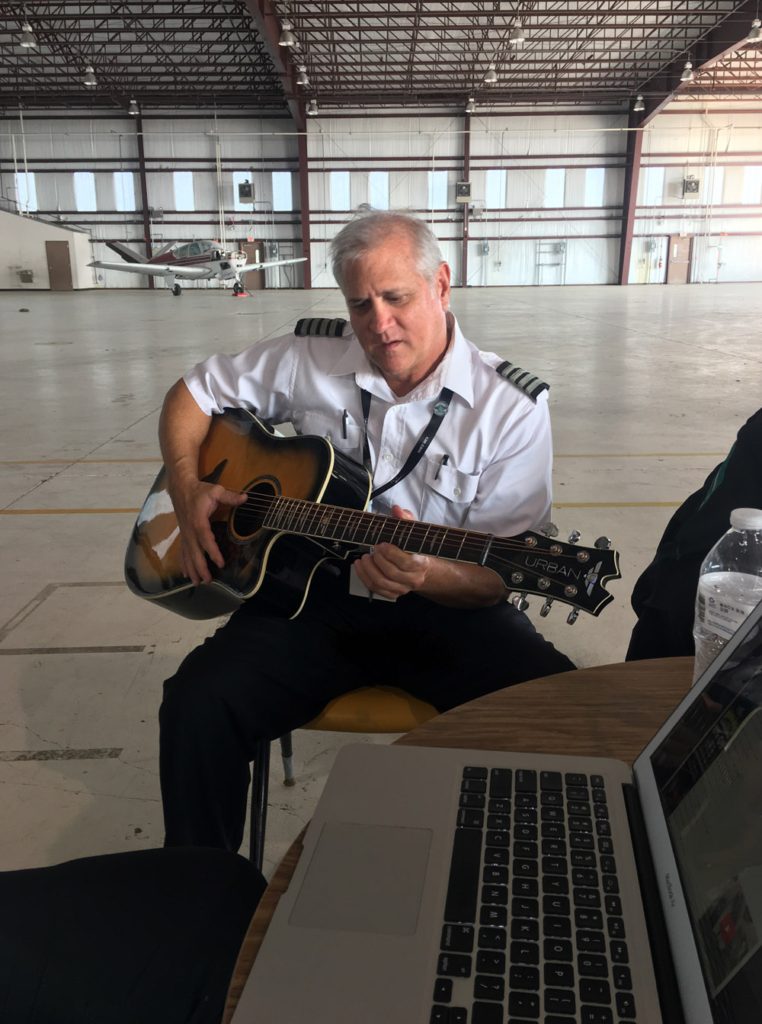

Given the short flying distances to our operations area, crews were required to be at the airport for the duration of their 12-hour shift, which had its own challenges. Flight teams that had arrived the earliest after the FEMA mobilization order had managed to secure the few air conditioned areas of the small operations building - and they guarded those areas as if they were staking a claim on a lucrative oil find. As a result, the MedCenter Air crews were largely relegated to the non air-conditioned hangar. Given the scope of the disaster that was unfolding just south of our base of operations, we were all sensitive enough to not complain, but it was pretty hot and sweaty in that hangar for the duration of your 12-hour shift. We set up “camp” around one of the center pillars that had dozens of power outlets and proceeded to make a home out of that location.

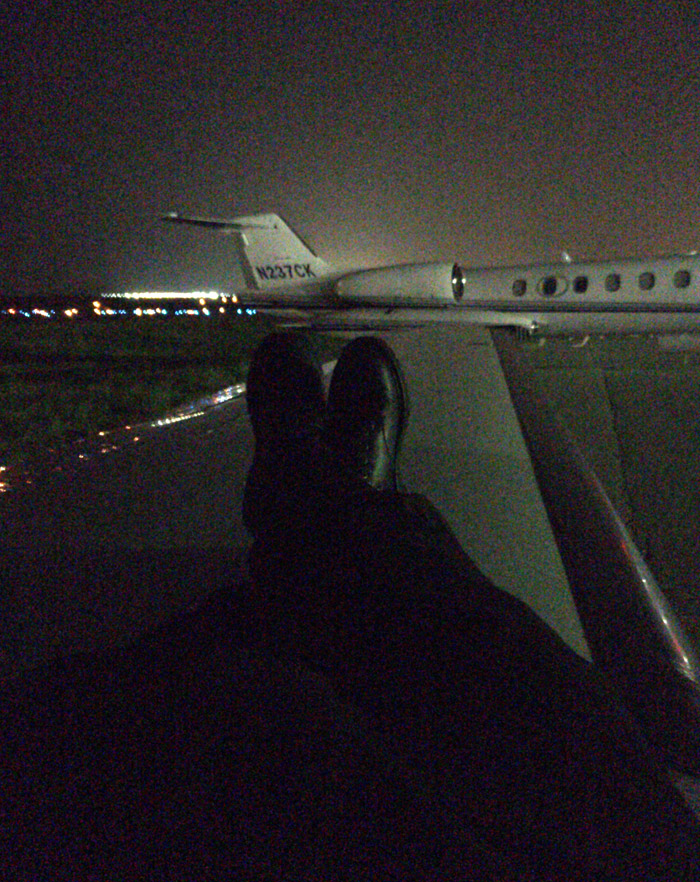

[caption id=“attachment_9012” align=“aligncenter” width=“400”] Given the heat in the hangar, I found it was sometimes better to sleep on the wing of the aircraft…[/caption]

Given the heat in the hangar, I found it was sometimes better to sleep on the wing of the aircraft…[/caption]

Shift change was a great opportunity to get the gouge from the previous crew - getting caught up on the rumor mill, exchanging operational notes, and discussing the day’s or night’s events. Though we shared hotel rooms, we were paired with someone from the opposite shift, allowing each crewmembers to have the room to themselves for their 12 hour off duty period.

[caption id=“attachment_9016” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] N209CM gets towed back to the FEMA flightline at the end of its mission.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9017” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

N209CM gets towed back to the FEMA flightline at the end of its mission.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9017” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Walking the flightline at night became a regular leg stretching exercise while waiting on the call…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9018” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Walking the flightline at night became a regular leg stretching exercise while waiting on the call…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9018” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Captain Xandi Newell post flights N265CM after a mission…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9020” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Captain Xandi Newell post flights N265CM after a mission…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9020” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Operations out of Temple were a 24 hour affair, with aircraft departing and arriving at all hours.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9021” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

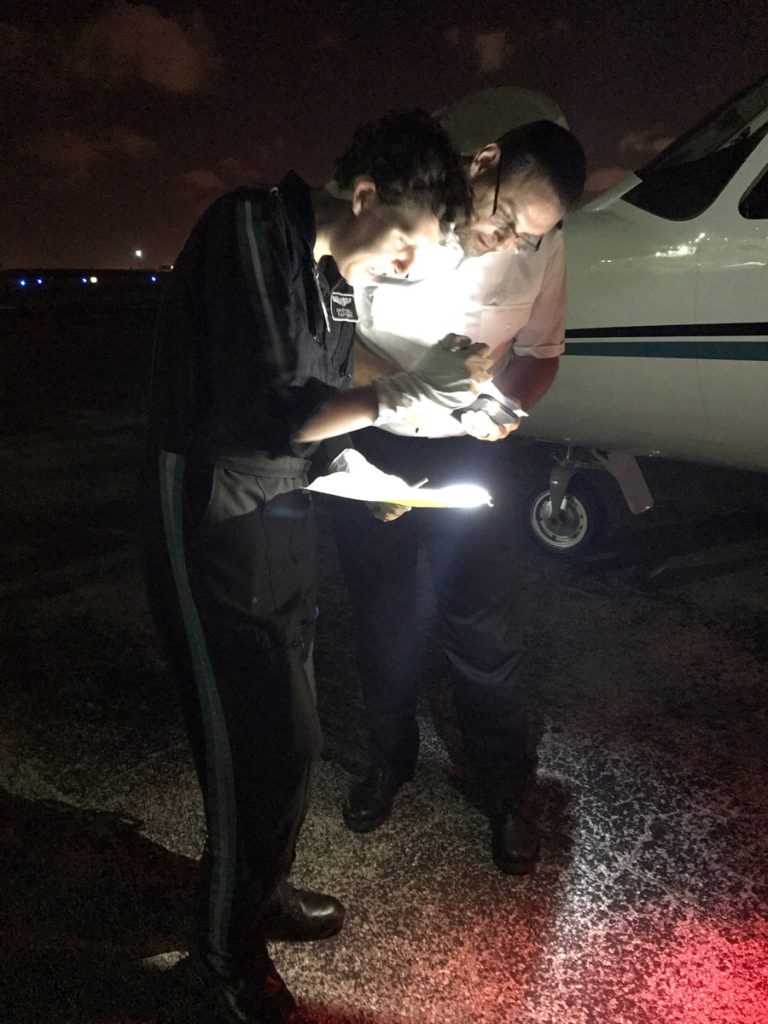

Operations out of Temple were a 24 hour affair, with aircraft departing and arriving at all hours.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9021” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Preflighting N209CM at shift change…[/caption]

Preflighting N209CM at shift change…[/caption]

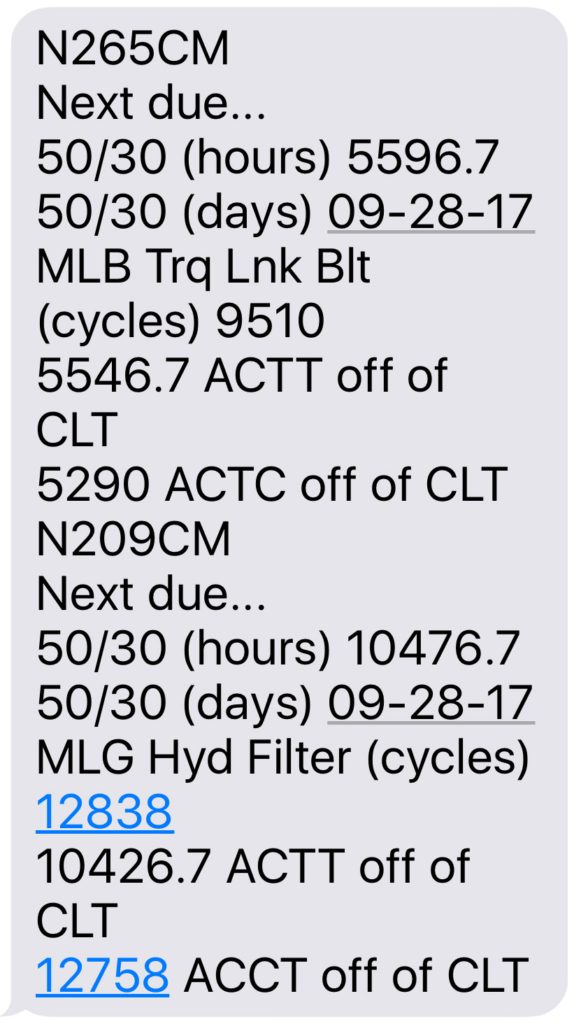

It is worth mentioning that throughout both of our hurricane deployments this year, our aircraft maintainers did an exceptional job of providing us reliable aircraft that performed flawlessly despite their distant locations. There was a 100% reliability and dispatch rate for the duration of both deployments and the maintenance department bent over backwards to provide inspections and servicing at ideal times and locations as we flew hours off the fleet. They did all of this while also supporting home base operations as well - a truly awesome job by Alan Reid, Rudy Waelz, and Tom Jasper!

[caption id=“attachment_9022” align=“aligncenter” width=“263”] Maintenance kept us apprised of our nearing maintenance due items.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9024” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Maintenance kept us apprised of our nearing maintenance due items.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9024” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Heavy flooding was readily apparent between Houston and Beaumont, TX.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9025” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Heavy flooding was readily apparent between Houston and Beaumont, TX.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9025” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Fueling up for the return flight to Austin, TX from Beaumont, TX.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9026” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Fueling up for the return flight to Austin, TX from Beaumont, TX.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9026” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Flooded communities and roads in Beaumont, TX.[/caption]

Flooded communities and roads in Beaumont, TX.[/caption]

After a week in Temple, we were deactivated by FEMA and we returned home to Charlotte. Already eyes were turning southeast as Irma loomed out in the Caribbean, with Jose hot on her heels. It would not be either of these storms that would bring MedCenter Air back into action though - instead, hurricane Maria would spawn in mid-September and rake across the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico as a Category 4/5 storm, devastating the islands in its path.

[caption id=“attachment_9028” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] The sun sets on N209CM’s mission in Temple on the afternoon FEMA deactivated MedCenter Air.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9029” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

The sun sets on N209CM’s mission in Temple on the afternoon FEMA deactivated MedCenter Air.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9029” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] N209CM on short final to Charlotte, NC - completing the Hurricane Harvey deployment.[/caption]

N209CM on short final to Charlotte, NC - completing the Hurricane Harvey deployment.[/caption]

Maria

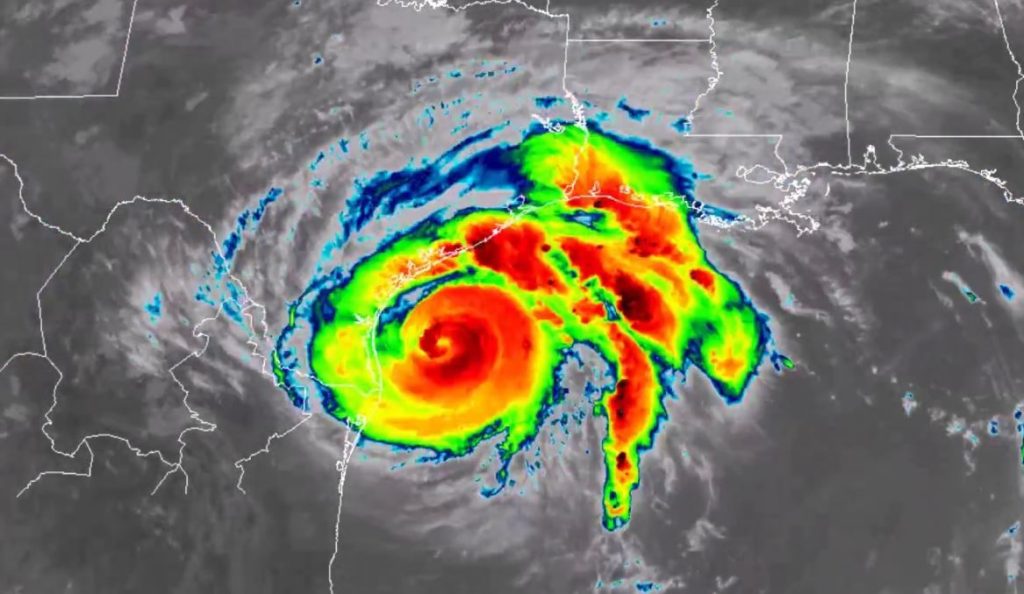

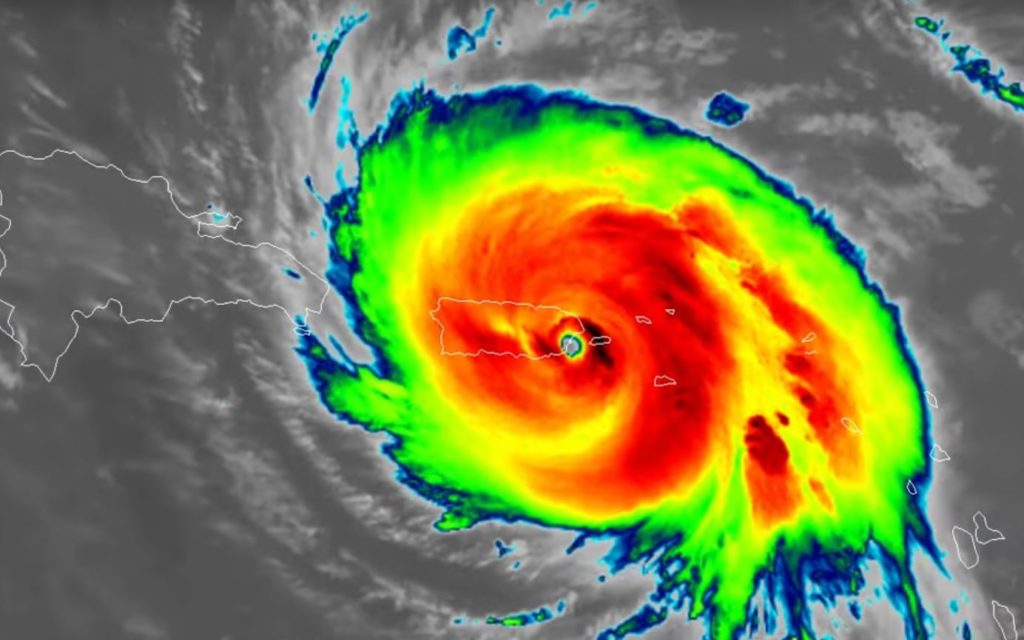

Just shy of three weeks after the completion of the hurricane Harvey deployment, the phone rang once again. From September 18-20, Hurricane Maria swept across the Leeward Islands and Puerto Rico, knocking out power to the entire island of Puerto Rico and doing massive damage to many islands to include St. Croix, St. John, and St. Thomas.

[caption id=“attachment_9032” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Hurricane Maria swirls as a high Category 4 hurricane as it makes landfall on the eastern tip of Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017.[/caption]

Hurricane Maria swirls as a high Category 4 hurricane as it makes landfall on the eastern tip of Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017.[/caption]

Within 24 hours of Maria’s landfall in Puerto Rico, MedCenter Air had, at the request of FEMA, an aircraft on the way to St. Petersburg, Florida (PIE) with enough staffing for 24 hour operations. In contrast to hurricane Harvey, the realities of the operational necessities made the Maria deployment a much more intense experience for MedCenter Air crews.

[caption id=“attachment_9033” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] The MedCenter Air fixed wing maintenance crews provided us with a tight aircraft that performed flawlessly despite relentless flying that racked up a month’s worth of hours in just days.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9034” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

The MedCenter Air fixed wing maintenance crews provided us with a tight aircraft that performed flawlessly despite relentless flying that racked up a month’s worth of hours in just days.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9034” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Preparations begin to move N265CM to St. Pete (PIE) for hurricane Maria response.[/caption]

Preparations begin to move N265CM to St. Pete (PIE) for hurricane Maria response.[/caption]

For hurricane Maria, owing to the anticipated stage lengths of over 1,300 miles, the King Air stayed home and we sent our Citation Ultra N265CM, which would be operating at near its maximum range for flights from the U.S. mainland to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Operating two shifts - four pilots and four medical crew were required to give round-the-clock coverage. Unlike hurricane Harvey, the shifts would not be set hours, and would instead depend solely on accumulated duty rest, a more challenging schedule that was difficult to maintain since acclimatization was nearly impossible to achieve.

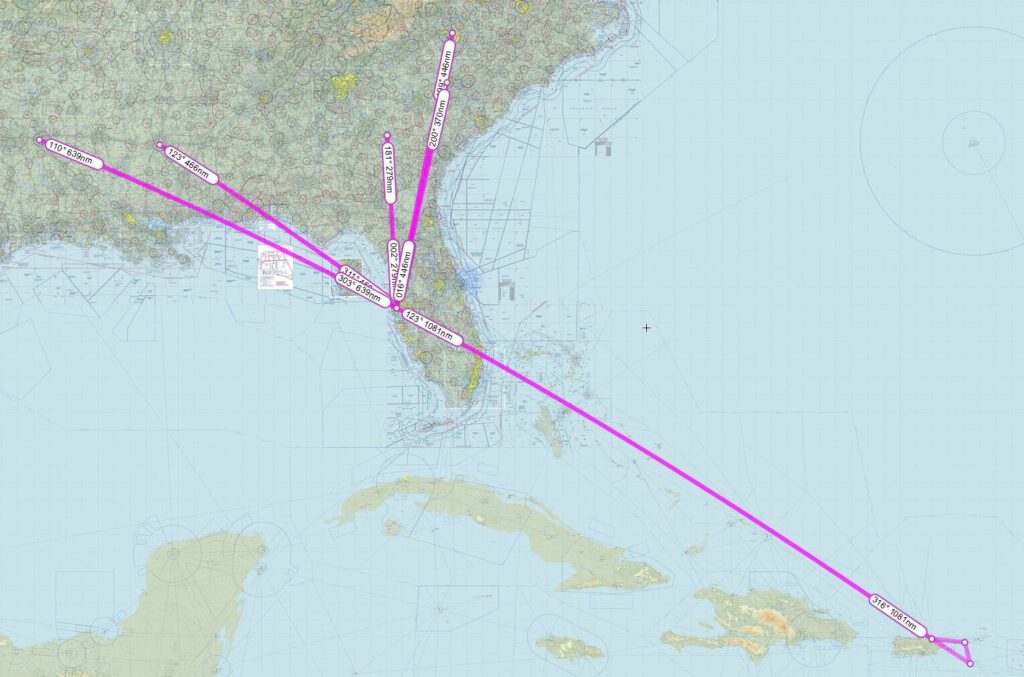

After an initial 24-hour stand-down on arrival in PIE for logistics and planning, FEMA put us into motion and our first flight launched as a domestic “wing to wing” transport where our crews took over patient care from a flight that had arrived in PIE from San Juan. Throughout the deployment, PIE would often serve as a “wing to wing” transfer stop, rest stop, and cargo and fuel loading depot. Due to the relatively large distances from Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to the interior of the U.S. mainland, crews from all flight departments were often reaching duty or flight time limitations, necessitating crew swaps and/or duty rest stops within the continental U.S.

[caption id=“attachment_9036” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A route map showing typical destinations for flights during our deployment.[/caption]

A route map showing typical destinations for flights during our deployment.[/caption]

Within 36-hours of arrival in PIE, having already started flying domestic “wing-to-wing” missions into the interior of the U.S., the plane made its first long distance transit to San Juan. For the next several days, we’d be skirting the still spinning hurricane Maria that was lurking just north of our tracks as it slowly moved off, paralleling the eastern seaboard of the U.S. mainland.

For the first week of operations to San Juan and the nearby islands, the conditions were probably the most interesting I’ve seen in my nearly twenty years with MedCenter Air. The hurricane had rendered inoperable the communications and radar relays across the eastern Caribbean, resulting in wide gaps in both VHF voice and ATC radar coverage, meaning that the fallback operating mode was to proceed VFR over fairly significant gaps. Each day, things seemed to get a bit better as repairs were made or temporary facilities were set up, but that first week had some interesting operational impacts that made all of us intensely aware of how careful we had to be with regards to aircraft range and fuel endurance. I’m proud to say that we performed all of the missions safely and with an eye toward making decisions that carefully weighed our capability against the realities of the environment. I can’t say how many times I used the term “we’ll do our best” in order to preserve options and not box ourselves in. Our Citation Ultra was “The Little Plane That Could” when compared to some of the longer legged Learjets, Hawkers, and Challengers that populated the FEMA ramp.

[caption id=“attachment_9040” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] N265CM lands in St. Pete (PIE) bringing a patient from St. Croix, USVI.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9041” align=“aligncenter” width=“400”]

N265CM lands in St. Pete (PIE) bringing a patient from St. Croix, USVI.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9041” align=“aligncenter” width=“400”] The author consults with MedCenter Air flight nurse Ashley Ezzell to find out the details of the patient - often we would not even have a name until the patient arrived at the aircraft.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9042” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

The author consults with MedCenter Air flight nurse Ashley Ezzell to find out the details of the patient - often we would not even have a name until the patient arrived at the aircraft.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9042” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Descending across the Atlanta metro area while continuing a medical evacuation out of St. Croix.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9043” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Descending across the Atlanta metro area while continuing a medical evacuation out of St. Croix.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9043” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] No rain - no rainbows…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9044” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

No rain - no rainbows…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9044” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Preparing to unload a patient at a domestic FEMA receiving facility.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9045” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Preparing to unload a patient at a domestic FEMA receiving facility.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9045” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Flight nurse Ashley Ezzell looks out over the Gulf of Mexico while we are on a duty rest period in St. Pete.[/caption]

Flight nurse Ashley Ezzell looks out over the Gulf of Mexico while we are on a duty rest period in St. Pete.[/caption]

Given the long distances to San Juan, fuel endurance was always of primary concern since our nearby alternates were of questionable quality given the on again/off again nature of the power supply on the surrounding islands. Crews used their collective experience to allow for good decision making and provide for alternative plans of action in the event of unforeseen (well, anticipated) circumstances. Stage lengths of around three hours were the norm, providing for enough fuel upon arrival to provide a comfortable buffer beyond the legal minimum fuel requirements. N265CM, our newer of the two Citation Ultras in our fleet, is a real performer and we routinely climbed to FL410 right off the bat despite temperatures aloft that weren’t all that conducive to that area of operations. When necessary to improve fuel numbers even more, crews would climb further to FL430 after burning off some of the initial fuel load.

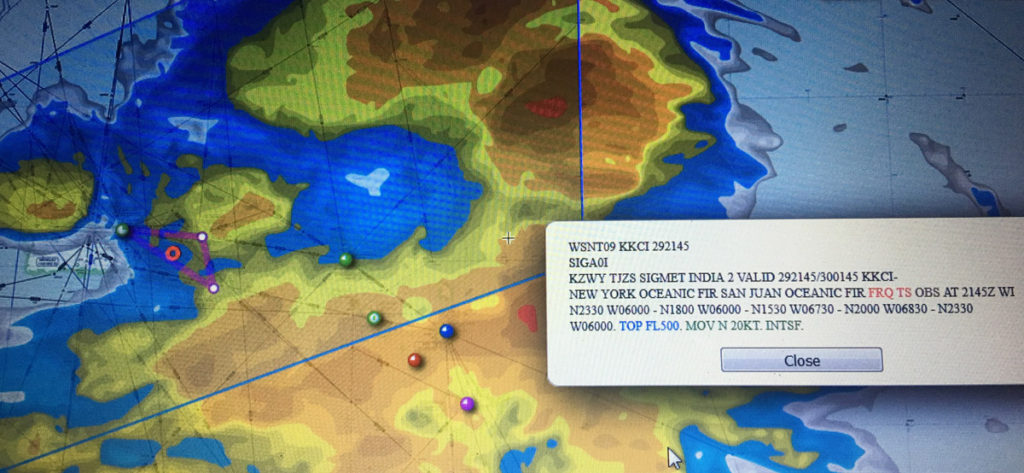

I will say that for the entire duration of our Maria deployment, we were all very lucky to be graced (by-and-large) with good weather that made fuel planning and flight execution relatively hassle free. A few thunderstorms had to be dodged, but large areas of poor weather were usually topped by our high flying jet. On those nights when widespread areas of poor weather threatened inter-island operations, we simply stated our operational constraints and that we’d be available for IFR flying between San Juan and the United States only.

[caption id=“attachment_9046” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Enroute to San Juan at a fuel economy altitude of 43,000’[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9047” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Enroute to San Juan at a fuel economy altitude of 43,000’[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9047” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Descending into a very dark Puerto Rico with the only lights being provided by those fortunate to have generators.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9133” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Descending into a very dark Puerto Rico with the only lights being provided by those fortunate to have generators.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9133” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] One of the only nights we decided we would not fly inter-island transfers due to a convective SIGMET hanging out over the islands.[/caption]

One of the only nights we decided we would not fly inter-island transfers due to a convective SIGMET hanging out over the islands.[/caption]

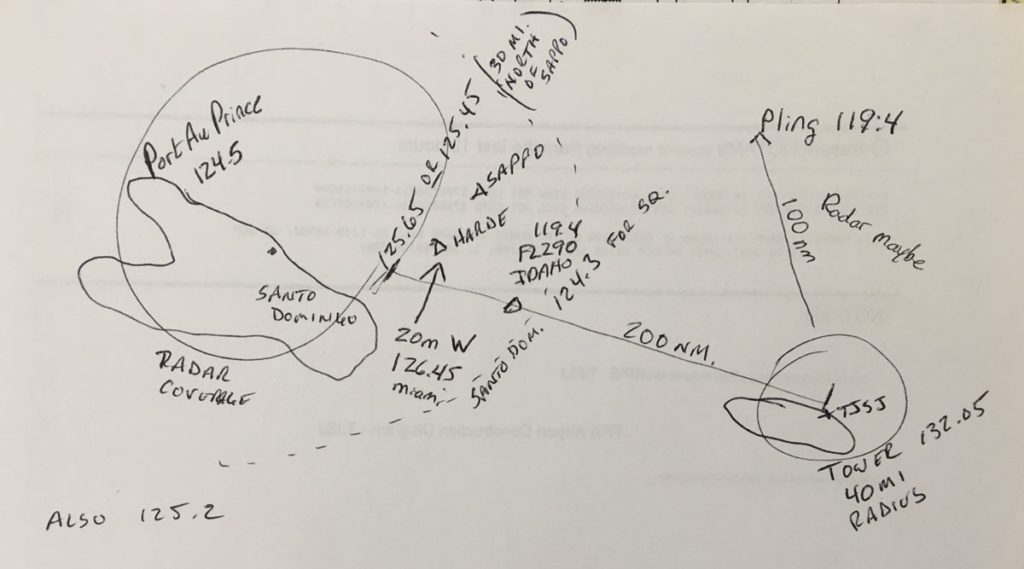

At the time I arrived on my first flight to San Juan (September 24 at 2AM) the Miami Center VHF communications and radar service ended right at the San Juan Oceanic sector near HARDE and SAPPO intersections about 185nm west of San Juan. At this point, a couple of days earlier, people were being told to cross these waypoints at a VFR altitude of 17,500’ (significantly affecting fuel burn) until reaching the 40nm radius from San Juan where VHF radio contact with San Juan tower could be established. The evening I flew out there, perhaps due to the lighter traffic load at 2AM, we were only descended to FL280 and were able to maintain that until a just opened temporary radar facility had us under radar contact approaching San Juan. In those first days, the hand drawn map that one of our other pilots (Capt. David Hounslow) created on his first trip out was invaluable gouge for those of us that would follow. The map would be further annotated by me, and eventually passed on to incoming pilots a week later.

Having only flown to San Juan a handful of times over the past couple of decades, I didn’t have much frame of reference for just how many lights I should be seeing as we lined up for our final approach in good visual conditions. It was eerily quiet at 2AM and as we crossed the coastline I could look down and see what I thought were a good many lights. Upon further scrutiny though, I realized I was only seeing about one or two lights per city block, and almost every high rise, apartment complex, and neighborhood was completely dark. Twinkling across the city were the blue lights of dozens of San Juan police vehicles that were roaming the streets, enforcing the 7PM curfew.

[caption id=“attachment_9050” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] The sparsely lit city of San Juan comes into view.[/caption]

The sparsely lit city of San Juan comes into view.[/caption]

After landing, we checked in with the “Air Boss” coordinating the aero-medical transports for FEMA and were driven to a nearby hotel in San Juan to go immediately into crew rest to be ready for the next day. In those early days after the hurricane, only a few hotels in San Juan had generator power, and a vigorous bartering system was in full swing to exchange supplies for rooms. I have no doubt that to get things done in any disaster zone, a certain flexibility is probably required. Needless to say, our hotel was comfortable given that nearly the entire island around us was in darkness with no electricity or running water. The carpet in our room was fairly saturated with water, and over the next week the smell of mildew and mold would increase daily - earning the nickname “The Swamp Room”.

In daylight the next morning, we looked out upon a battered, but largely intact city around our hotel. No doubt the close proximity of all the buildings had a bit of a sheltering effect, so the downtown area really wasn’t representative of the more intense destruction island wide. Still, most of the trees had their leaves blown clear off, although some of the palms seem to have weathered the storm. Many trees were completely blown over, and all manner of roofs, awnings, signs, and other structures were either damaged or destroyed. Without power, most businesses were still shuttered, but people were already at work clearing out debris and starting the process of getting back on their feet.

[caption id=“attachment_9052” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Flight nurse Jodi Harte looks out over the battered patio area of the hotel and across at another highrise that had many rooms gutted from the winds and rain.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9053” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Flight nurse Jodi Harte looks out over the battered patio area of the hotel and across at another highrise that had many rooms gutted from the winds and rain.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9053” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] View from the 7th floor of the Verdanza Hotel, San Juan.[/caption]

View from the 7th floor of the Verdanza Hotel, San Juan.[/caption]

On the drive back to the airport the next morning, we were able to see the widespread destruction that we hadn’t seen during our evening drive to the hotel. Highway signs were missing, hundreds of trees were blown down, many power poles were either snapped or crushed under other debris, and almost every structure had damage of some sort or another. The power problem in Puerto Rico has been somewhat exacerbated by the fact that many of the power poles that were replaced after Hurricane Hugo in 1989 were built to be more sturdy out of concrete and rebar. Despite the reinforcement, those poles also were toppled by Maria’s winds, and clearing concrete poles is not as simple as taking a chainsaw to them - they require heavy equipment to dismantle and move. Long lines of people waited at food stores, banks, and gas stations - with people setting up folding chairs in line - an indication of how long they were having to wait.

The scene at the airport FBO was also pretty impressive. Women, children, the elderly, and family pets were all packed into the small FBO building, spilling out into the parking lot as the families of government and military personnel arrived to be evacuated on all kinds of aircraft that must have been chartered by individual government agencies. Everything from PC-12s to Boeing 737s were loading people to take to the United States. On multiple occasions I was approached by people, who, seeing my pilot uniform, enquired as to whether I had any seats available on my aircraft. It was a small version of the Fall of Saigon, and it would get busier as the week progressed.

[caption id=“attachment_9056” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] One of the more calmer moments at the FBO in San Juan where government workers, families, and aid workers were waiting for flights to the U.S. mainland.[/caption]

One of the more calmer moments at the FBO in San Juan where government workers, families, and aid workers were waiting for flights to the U.S. mainland.[/caption]

Our tasking for that day was to transport some FEMA contractors, military specialists from the CDC, and some equipment the short distance from San Juan to St. Croix, drop them off, then take a patient from St. Croix to a FEMA receiving facility in the United States. The FBO and ramp in San Juan was a mad house and, in that first week, internet and cell phone service was sporadic at best. Filing flight plans, checking weather, and just communicating with people back home was always a patchwork of grabbing cell service when you could, and using the Iridium satellite phone when other methods weren’t available. By the end of my second week flying in and out of San Juan, cell reception was still spotty, but getting better, and internet service at the FBO and hotels was fairly good, allowing for Skype type calls even when the cellular network wasn’t working. As well, we were issued short range radios from the airport FEMA VIPR Base (Virgin Islands/Puerto Rico) ostensibly to get a hold of us by driving in front of our hotel and calling on the radio if we were being dispatched.

[caption id=“attachment_9058” align=“aligncenter” width=“400”] “VIPR Base, VIPR Base, come in VIPR Base…”[/caption]

“VIPR Base, VIPR Base, come in VIPR Base…”[/caption]

Aware that our first tasking might take us on a short range flight to one of the surrounding islands, we had held off on fueling the aircraft the night before so that we could be assured of making landing weight if we had a short hop. Again, in the early days of the deployment, the fuel situation in both St. Thomas and St. Croix was a bit in flux, with St. Thomas having none (or at least of questionable quality), and St. Croix being reported to have some. We brought our fuel load up to 4,000 lbs. to allow us to fill the aircraft with personnel and supplies for the fifteen minute hop over to St. Croix.

During the first week of the deployment, all operations outside of the immediate San Juan area were VFR only. In fact, during the first few days after the hurricane, it was VFR operations only all the way to the aforementioned 185 mile fixes west of San Juan, providing for some interesting radio interactions as Miami Center cancelled IFR on everyone from small piston aircraft to Jet Blue Airbuses and military C-17s. This being the case, operations were very much head-on-a-swivel, keep an eye on the TCAS, and avoid clouds to remain VFR.

By the second week, a temporary, extended range radar had been set up somewhere in Puerto Rico that largely gave Miami Center their eyes back, as well as their VHF radio ability. For the entirety of our flying to the islands however, IFR clearances for the full distance to St. Croix were not available, nor were IFR releases or approaches from or to the islands available, although that was due to change by the third week as the U.S. Air Force was on the brink of establishing data connectivity between their temporary control towers and the FAA facilities. All of the people flying out there were very fortunate in that the weather stayed fairly decent for at least the initial two weeks. Occasional thunderstorms and rain squalls would move through, but the trade winds tended to push them out of the area in short order.

For out little Citation, it was a bit of a tense first hour of flight coming out of St. Croix if we were returning to the United States, because due to the lack of radar east and south of San Juan, you were generally kept low (below 18,000’) until you could both get in radar contact, and receive your IFR clearance to climb. Even after the first week, IFR clearances were generally only being issued to climb to FL280 until 185 miles west of San Juan, which did take a toll on our fuel endurance. In order to make it up, most of us were climbing to FL430 for our return legs to St. Pete. In a real pinch, we had the ability to drop into Palm Beach if the fuel looked iffy, or even a mid point stop of Providenciales, Turks and Caicos, or a course reversal back to San Juan. Fortunately, clearances were obtained in short enough order that we never had to do that, but others that were stuffed down below FL180 for extended periods of time occasionally had to divert due to fuel burns.

[caption id=“attachment_9073” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] We saw a lot of sunrises and sunsets over the weeks.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9074” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

We saw a lot of sunrises and sunsets over the weeks.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9074” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Westbound toward St. Pete at FL400.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9075” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Westbound toward St. Pete at FL400.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9075” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] The rising sun casts shadows from some build ups on the horizon.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9076” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

The rising sun casts shadows from some build ups on the horizon.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9076” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A ravaged San Juan - most of the greenery blown away with the winds, leaving the area mostly brown.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9077” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

A ravaged San Juan - most of the greenery blown away with the winds, leaving the area mostly brown.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9077” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Captain Blanton as we get ready to load up to head for St. Croix.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9078” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Captain Blanton as we get ready to load up to head for St. Croix.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9078” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Though nearly none of the Caribbean Islands were untouched by hurricanes this year, the storms couldn’t wash away the natural beauty of their geography.[/caption]

Though nearly none of the Caribbean Islands were untouched by hurricanes this year, the storms couldn’t wash away the natural beauty of their geography.[/caption]

By the mid point of the first week, I think most people could smell us coming before we actually arrived. Being the Caribbean in September, temperatures were fairly warm, and the humidity was through the roof. It only took a few minutes of moving around loading patients or supplies before your clothes were drenched through with sweat. I had two standout memorable days during my near two weeks flying down there - the first was my birthday, when my awesome crew surprised me with a card and birthday treats, and the second was the beginning of the second week when I managed to slip away for two hours to find a washer and dryer while on a crew rest period in St. Pete. The smell of fresh clothes and laundry detergent was unbelievably delicious.

[caption id=“attachment_9089” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] My incredible first week crew: Me, Jodi Harte, Ashley Ezzell, and Michael Blanton. As well, Jenny Van Dongen was our constant cheerleader and supporter from St. Pete.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9090” align=“aligncenter” width=“500”]

My incredible first week crew: Me, Jodi Harte, Ashley Ezzell, and Michael Blanton. As well, Jenny Van Dongen was our constant cheerleader and supporter from St. Pete.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9090” align=“aligncenter” width=“500”] Birthday sundae at 1AM in St. Pete.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9091” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Birthday sundae at 1AM in St. Pete.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9091” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Heaven after a week in sweaty clothes…![/caption][caption id=“attachment_9092” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Heaven after a week in sweaty clothes…![/caption][caption id=“attachment_9092” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] The requirement to constantly travel with our bags meant packing up for every movement - or not unpacking at all.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9093” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

The requirement to constantly travel with our bags meant packing up for every movement - or not unpacking at all.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9093” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Another clown car moment…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9095” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Another clown car moment…[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9095” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Loading supplies in St. Pete to take to San Juan.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9096” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Loading supplies in St. Pete to take to San Juan.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9096” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Moon setting over the Gulf of Mexico enroute to Shreveport, Louisiana.[/caption]

Moon setting over the Gulf of Mexico enroute to Shreveport, Louisiana.[/caption]

By the end of the first week, it was time to swap out the pilots and medical crews for fresh volunteers. Myself and flight nurse Chris Travis volunteered to stay for an additional period to help transition the incoming crews to the operation and provide for a bit of overlap. Crew swap day was definitely a sad moment for me and my crew as we had really grown close over the previous week and breaking up the team was very difficult. A company King Air was flown down with the new arrivals and the stinky Week One crews clambered aboard to fly back to Charlotte. Our maintenance department also took the opportunity to send down Rudy Waelz to give N265CM a good look-over, complete some routine maintenance, and get her ready to go for the second week. I can’t stress enough what a fantastic job our maintenance team did at giving us a good aircraft to fly for the duration of our deployment.

[caption id=“attachment_9097” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] The outgoing and incoming crews have a quick lunch to pass the baton and brief one another.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9098” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

The outgoing and incoming crews have a quick lunch to pass the baton and brief one another.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9098” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] N207CM brought in the new crews and supplies for N265CM.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9099” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

N207CM brought in the new crews and supplies for N265CM.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9099” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Rudy Waelz did a fantastic job of getting N265CM back to tip top shape for Week Two.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9100” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Rudy Waelz did a fantastic job of getting N265CM back to tip top shape for Week Two.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9100” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] The Week One crew heads home to Charlotte.[/caption]

The Week One crew heads home to Charlotte.[/caption]

[caption id=“attachment_9102” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Nearly every tree and bush in St. Croix and St. Thomas were stripped of their green leaves. The once lush island is mostly brown now - but is sure to recover over time.[/caption]

Nearly every tree and bush in St. Croix and St. Thomas were stripped of their green leaves. The once lush island is mostly brown now - but is sure to recover over time.[/caption]

As the second week started, the general evacuations (non medical) from Puerto Rico seemed to increase as more and more people began to realize the scope of the damage. Those that waited through that first week probably soon realized that it might be weeks or months longer before power and/or water was restored to some areas. The zoo that was the FBO in San Juan continued to see increasing passenger volume and that was causing some pretty decent traffic jams leading to the airport. Since we were being put in duty rest at our hotels in order to preserve us for the very long flights to the mainland we were doing, we would be called and then have to make our way to the airport. Some crews reported taking almost two hours to reach the airport for a drive that is only a few miles total. As the result of these and other logistics obstacles, the rumor toward the tail end of the second week was that operations would soon be moved over to St. Croix.

[caption id=“attachment_9103” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Traffic getting to the airport became more and more challenging.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9104” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Traffic getting to the airport became more and more challenging.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9104” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A C-17 departs San Juan.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9105” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

A C-17 departs San Juan.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9105” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] A Marine UH-1Y loaded with supplies heads out of San Juan airport.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9107” align=“aligncenter” width=“500”]

A Marine UH-1Y loaded with supplies heads out of San Juan airport.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9107” align=“aligncenter” width=“500”] We renew an old acquaintance in St. Croix - Allan Adler used to be a dispatcher for MedCenter Air and he now helps manage AeroMD in St. Croix.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9109” align=“aligncenter” width=“500”]

We renew an old acquaintance in St. Croix - Allan Adler used to be a dispatcher for MedCenter Air and he now helps manage AeroMD in St. Croix.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9109” align=“aligncenter” width=“500”] Unloading a patient at a FEMA receiving facility in Columbia, SC.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9110” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”]

Unloading a patient at a FEMA receiving facility in Columbia, SC.[/caption][caption id=“attachment_9110” align=“aligncenter” width=“680”] Our Week One team…[/caption]

Our Week One team…[/caption]

By the mid point of Week Two, things had started to slow down a bit as we theorized that FEMA was gearing up for the move to St. Croix. After a few days the home office in Charlotte started looking at replacing the two of us that had stayed through the first week. In staying with the theme of everything changing every ten minutes, many plans were made for getting us home and swapping us out with incoming crewmembers, most of which failed to happen. Eventually, a commercial flight to San Juan was secured for our two replacements, and upon their arrival me and Chris Travis went about trying to find a way home. We went from the ones being asked if we had any seats available, to being the ones asking for seats. We spent one entire day and night at the airport waiting for an outbound medical flight that we might be able to hop on, but all were at their seating capacity or near their max weight. We did hop on one aircraft that was headed for St. Pete, but a maintenance item that we weren’t sure would get fixed quickly led to us electing to stay an additional night in San Juan.

The next morning, through some very fortunate connections, we were able to secure seats on a DC-8 run by a church based aid group out of Greensboro, NC called Samaritans Purse. We arrived at the airport around 8AM to await the departure, but the outbound crew became stuck in a three hour long traffic jam due to the President arriving to tour San Juan. Toward mid-afternoon, the traffic cleared, the TFR was lifted, and we were thrilled to get seats on the GSO bound DC-8. It was interesting to talk to the pilots of the DC-8 and learn that their aircraft had left the factory floor on December 24, 1969!

[caption id=“attachment_9111” align=“aligncenter” width=“500”] Chris Travis and I board the Samaritans Purse DC-8 to Greensboro, NC.[/caption]

Chris Travis and I board the Samaritans Purse DC-8 to Greensboro, NC.[/caption]

Upon arrival in GSO, we were shuttled back to Charlotte by a MedCenter Air vehicle, went through a quick medical check and debriefing, and we were back home by midnight. It was an interesting re-entry into the normal world in that I had been running on blocks of four and five hours of sleep for the preceding twelve days. It was hard to shut off from that, and the first couple of nights I was home, I would wake up not knowing where I was and thinking I was supposed to have my phone and radio near me ready to go flying. It was obviously a bit of self induced stress that I had been carrying along and it was just taking some time to settle out. After a couple of days back in Charlotte, I was asked if I could return to San Juan with a new crew that would be swapping out with the Week Two crew and I agreed to go. The four of us replacements had taken an airliner down to Tampa to try to hop a repositioning medical flight to San Juan, but as soon as we touched down in Tampa we received word that MedCenter Air had been demobilized by FEMA at the end of the second week. A mixture of relief and disappointment flooded me. We were immediately rebooked back to Charlotte and we arrived home later that evening. The remaining crews in San Juan set up a shuttle from San Juan to St. Pete, and then on to Charlotte in an impressive display of demobilization planning.

I think we all agree that we did the best that we could with what we were tasked to do down there. N265CM flew nearly 80 hours worth of flight time without a single squawk other than normal wear and tear items - a testament to our maintenance crews back at home. The support we received from Carolinas Healthcare System, MedCenter Air within, and from our certificate holder (GAMA Aviation) were fantastic.

Of course, the story doesn’t end with our demobilization. On the day I flew out of San Juan at the end of Week Two, I walked into “VIPR Base” and into the waiting area behind the FEMA dispatching room and there were eight pilot and medical crew members occupying the room, all dressed in matching blue flight suits. In one of those moments, that seem to be increasing as I get older where the distance from my brain to my mouth becomes ever shorter, I went ahead and blurted out my first reaction: “Man, you guys smell good…!” They were new arrivals from the mainland. Teams are rotating in and out, and the local air medical transport teams down there are probably getting little to no respite. Twenty four hours a day they are down there moving patients, supplies, and personnel. Chipping away at the need - and it is clear the need remains. I expect at some point we might be asked to rotate back down there, and I know I won’t be alone in volunteering to go. It was an extraordinary deployment that we will all remember for the rest of our careers. Our thoughts and prayers are with those still suffering without power and water in Puerto Rico and the neighboring islands, and it is our hope that they will be fully restored in the near future.

Chris Frishmuth

Those wishing to donate to the relief efforts for Hurricane Maria can find information here: Direct Relief - Maria

Those wishing to donate to the relief efforts for Hurricane Harvey can find information here: Direct Relief - Harvey

Additional information about aid to Puerto Rico can be found here: United For Puerto Rico

[gallery columns=“4” size=“large” ids=“9118,9119,9120,9121,9122,9123,9124,9125,9126,9127,9128,9129”]